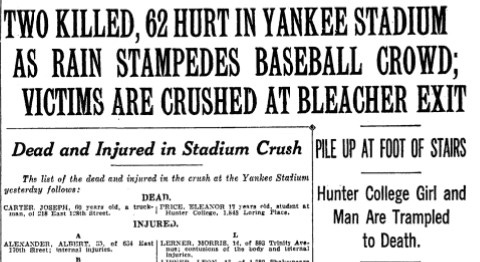

Today, May 19, 2023, marks the 94th anniversary of the Yankee Stadium stampede, an event that killed two people and injured more than 60 others.

Eleanor Price and her little brother, George, were all set to walk to the ballpark when their home telephone rang.

It was George’s friend asking if he and George could spend the day together.

George and Eleanor had planned to go to a double-header at Yankee Stadium that Saturday afternoon between the hometown Yanks and Boston Red Sox. Eleanor loved baseball, and she hadn’t been to a game all season, which was already a month old.

The siblings talked it over and reconfigured their plans. George would go with his pal, and Eleanor would spend the afternoon at a nearby movie theater.

Another double header was slated for Sunday. They’d go to at least one of those games, even though the weather forecast called for a cooler day with a chance of rain.

While the young brother and sister were on their separate ventures, the Yankees busted a five-game losing snap and swept past the Sox, winning 5-2 and 5-0 that Saturday. Lefty Herb Pennock made Boston batters look feeble in the first game in front of 45,000 fans. The win put the Yankees back in second place early in the American League race, ahead of the third-place St. Louis Browns and behind the front-running Philadelphia Athletics.

In the second contest, right hander George Pipgras tossed what The New York Times’ John Drebinger called a “brilliant one-hit game,” and “close to a masterpiece of pitching perfection” in the 5-0 victory.

It was a splendid day at the ballpark for the hometown crowd.

George and Eleanor missed it.

Sunday, however, was a new day. The brother and sister left their residence at 1848 Loring Place in the Bronx, a little more than a 30-minute walk to Yankee Stadium, in time for the 1:30 p.m. first pitch.

The air was a bit warmer than expected on this 19th day of May, with the temperature reaching the high 70s.

George and Eleanor settled in the right field bleachers. Ruthville, it was called. It earned that moniker because of its popularity with young fans – many of whom could not “afford aristocratic grandstand seats,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle suggested – wanting to sit behind the Babe as he roamed right field. It also was the landing pad for many of the Bambino’s gargantuan home runs.

Given their ages – George was 14, and Eleanor was 17 – they fit right in with the youthful Ruthville gang. But, older fans populated the bleacher seats, too, like Joseph Carter, a 60-year-old truck driver from Manhattan’s East Street. The siblings did not know Carter, but less than 24 hours later their names would become linked together in black ink on newspapers nationwide.

As the game began, the large crowd, decked out in straw hats and summer clothes, appeared in good spirits. They enjoyed the bright sunshine that warmed their faces and brightened the Bronx sky.

They relished in the minutes of calm before the storm.

*****

More than 50,000 fans gathered at the ballpark on this Sunday, eager to watch the Yankees, winners of the last two World Series, take on the Red Sox, if not for both games, then at least the early contest. Too, they wanted to see Ruth and Lou Gehrig, the Yanks’ two big sluggers, pound Boston pitching.

The hope was, of course, both would smack home runs. That would send the crowd into a frenzy, particularly if Ruth hit one. He already had six homers during the young season, and he was chasing 60, the record number he had blasted in 1927. Ruth also had his sights set on Gehrig, who was off to a torrid start with eight homers and a .341 batting average.

Hitting third in skipper Miller Huggins’ order, Ruth got his first chance in the bottom of the first inning. Earle Combs led off with a walk and moved to second when Mark Koenig grounded out to second. Ruth strolled to the plate to face Boston pitcher Jack Russell.

With Combs leaning far off second – he was halfway to third – it tempted Red Sox catcher Charlie Berry into a pick-off attempt. As soon as Berry sprang to throw to second base, Combs bolted toward third. Second baseman Bill Regan took the catcher’s throw and fired over to third base. His throw was wide. Comes was safe, and now only 90 feet from home.

The Bronx faithful hummed with the possibility of an early run.

Still with only one out, Russell stood on the mound to face Ruth. The crowd begged for a moon shot and a Yankees lead. They got the lead, but not from a Ruthian blast. Instead, the slugger grounded to second, where Regan fielded and threw to first to oust the Babe.

Koenig raced home for a 1-0 Yankees advantage.

Errors plagued the Red Sox in the first. Hitting after Ruth, Gehrig grounded to first baseman Phil Todt, who fumbled the ball. Next it was Bobby Reeves’ turn for a mishap. Bob Meusel hit a sharp grounder to the Sox third baseman, who fielded it cleanly, but his errant throw to first allowed Meusel to reach safely and Gehrig to go to third.

The Yankee Stadium crowd buzzed with excitement.

New York pitcher Fred Heimach quieted Boston hitters in the second and much of the third, allowing only a lead-off single to Regan. Regan, however, was quickly erased from the base paths when he was caught trying to steal second. Two quick groundouts followed and the stadium was cracking again with the site of Ruth walking to the plate.

The Babe hadn’t hit a home run in nine days. He was due and the crowd knew it, even though the big fella was still ailing from a sore, swollen wrist he injured more than a week earlier when the Yankees were in St. Louis.

The Red Sox hurler did all he could to avoid being the slugger’s latest victim, but to no avail. Sore wrist and all, the Babe sent Russell’s pitch screaming deep into the Bronx sky. A “noisy crash,” is how one newspaper described it.

On contact, the Babe knew the ball was heading for the bleachers. Russell knew it, too. So did the roaring fans.

It was a goner.

Ruth put little effort into the hit, New York Times writer John Drebinger observed in the next day’s newspaper. “He appeared to merely reach for the ball, but he met it squarely and it traveled in a low arc to Ruthville.”

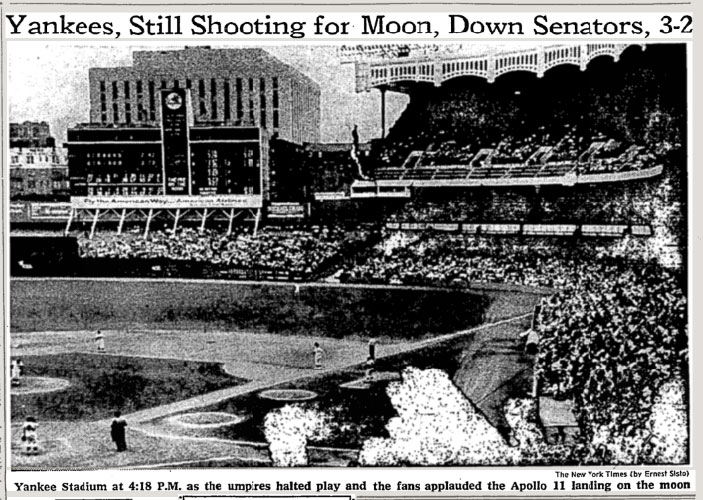

As he concluded his trip around the bases, Ruth doffed his navy-blue cap and touched home. The adoring crowd greeted the slugger with a thunderous ovation. This was the show 50,000 spectators came to see at this warm Sunday matinee, something George and Eleanor would have missed the day before.

Ruth’s blast put New York ahead 2-0, and it inched him closer to Gehrig in the home run race… for the moment

Before the crowd could settle from its delirium, the Yankee first baseman walloped a Russell pitch to deep left field “where Lou seldom hits,” the Times reported. The ball soared over Doug Taitt’s head. The Sox left fielder chased the ball as it rolled deep into the outfield and on to the warning track.

Gehrig ripped around the bases, looking faster than 3-year-old thoroughbred Clyde Van Dusen had the day before in the Kentucky Derby mud and slop. The Yankee Stadium crowd became more jubilant as Red Sox fielders quickly relayed the baseball toward home plate, hoping to nab the streaking Gehrig. Spectators roared louder as Lou skidded head first through the dirt into home, soiling his white-pinstriped uniform, kicking up dust and a rousing cheer all around him.

“Safe!” was the umpire’s call.

The champs, playing hard-nosed baseball to earn their way back to first place, suddenly led the Red Sox, 3-0.

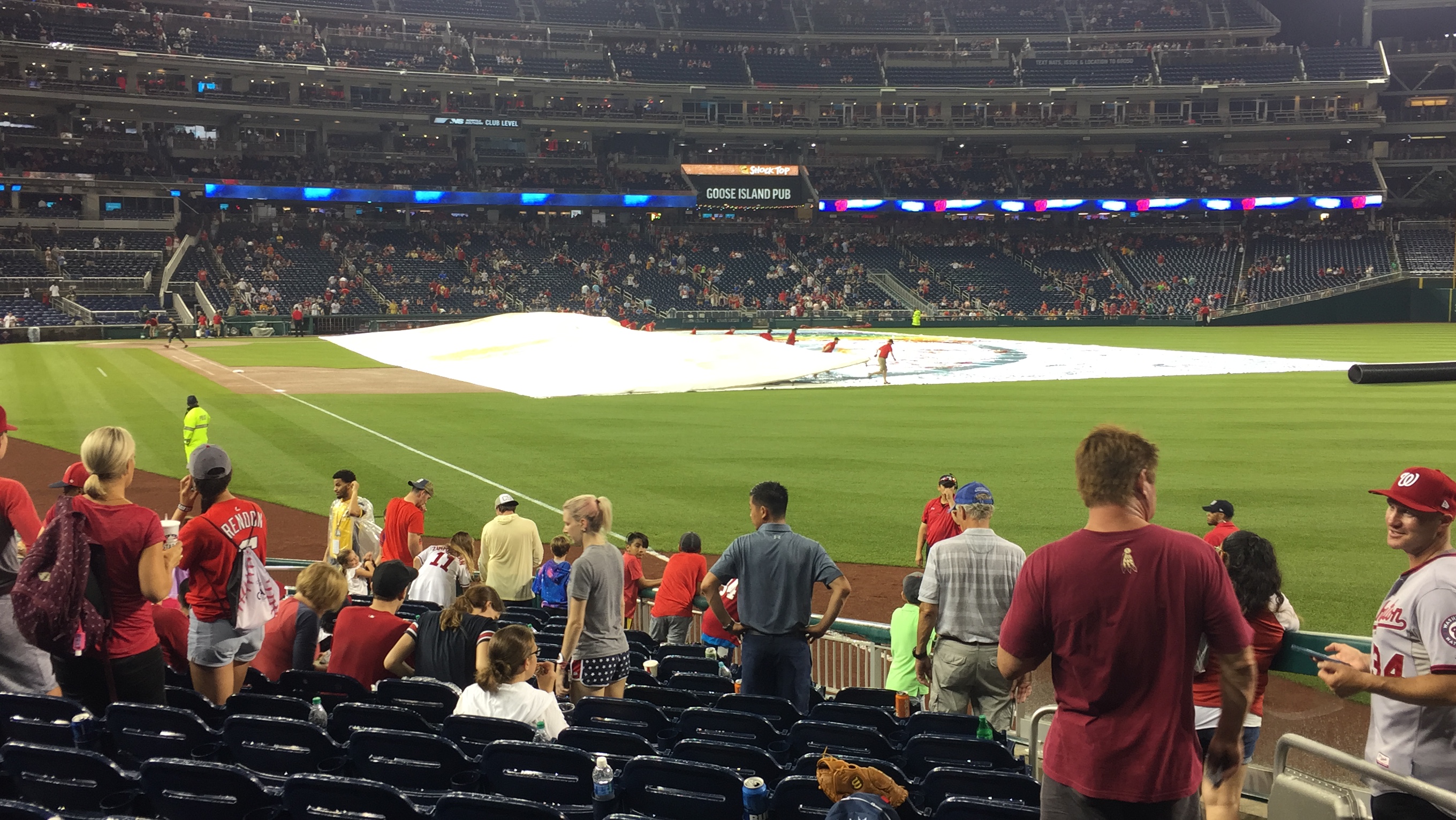

In the fifth, a bit of a damper fell over the festivities as storm clouds accumulated and loomed over the large darkening ballpark. Soon, a light rain fell. Umpires Brick Owens, Bick Campbell and Harry Geisel discussed the playing conditions and decided to continue on with the game.

A few fans in the bleachers left their seats, perhaps choosing to care for their Sunday bests. They gathered and stood at the southernmost exit of Ruthville – a quick exit, they likely surmised. But also, it would be relatively easy for them to peek at the playing field if something exciting transpired.

The Sox put a couple of runners on base in the top of the fifth, but the Yankees quickly erased the threat.

The threat of rain, however, intensified.

As the game moved into the bottom of the fifth, the stadium crowd again grew restless and excited with anticipation knowing that Ruth was due up second, and Gehrig was to follow.

They were weary, however, of the ominous storm clouds that hovered as the clock struck 3 p.m.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, reporting from the scene, described an “inky pall” hanging over Yankee Stadium that made the grass look a “sickly green.”

The light rain grew steadier as Koenig quickly grounded out. The wind whipped in, forcing flags stationed on the stadium roof to stand straight out.

The Babe hurried to the batter’s box, and the crowd, now getting soaked, continued to look on hoping to see one more Ruthian, cloud-bursting clout.

Residents of Ruthville rose as the larger-than-life figure stood beneath the thunderous sky.

Russell dug in and threw toward the plate.

Ruth swung through the rain drops.

But, his contact was weak. The slugger merely grounded to the first baseman for the second out of the inning.

Disappointed Ruthville residents groaned.

But almost immediately afterward, Gehrig approached the plate, ready to once again take his hacks against the Red Sox hurler. The crowd again worked itself into a frenzy, begging the Iron Horse to deliver another home run.

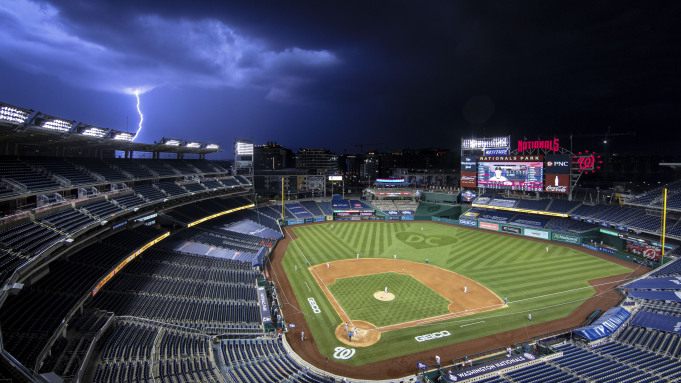

But, before further action could happen on the field, a calamitous boom rocked the concrete and steel ballpark as if the earth were crumbling.

A lightning bolt ripped through the clouds and across the Bronx sky. It sounded like “machine gun fire,” the Brooklyn Eagle reported. The rain intensified into a deluge. Umpires waved players off the field.

Spectator Harry Becker and a couple of his pals had commuted from Hartford, Connecticut, to attend the game and sat in the grandstand. Later in the evening, Becker recalled the stadium becoming “dark as night, so dark that lights were turned on.”

“A solid sheet of water, so dense as to obscure from sight objects only a few score feet away, roared down,” The Times reported. The 5,000 or so Ruthville occupants shrieked in panic as they sought shelter from the storm.

As clock hands landed on 10 past 3, fans in the right field bleachers quickly began a mass exodus to escape the storm. Many raced toward the southern exit, converging from both sides, pushing and shoving one another as they went along the 35-foot long, 12-foot wide walkway.

That exit led down 14 wooden stairs, which from the top was about an eight-foot vertical drop to the dirt floor below. There was a passageway underneath the bleachers that ran back about 30 feet from the ballyard’s outfield fence. That passageway joined another path to an exit. The latter was walled with chicken wire supported by two-by-four posts.

As the storm intensified, so did the urgency to escape.

“The crowd tore and trampled one another in a witless frenzy,” the New York Daily News reported.

Those in front tried to push back, urging calm, but the force of thousands was too heavy to fight.

“Then a sudden jostle from the mob upset the balance of those at the foot of the stairs,” The Times reported. One fan near the front lost his footing on the wet, slippery wooden steps and fell to the ground. Others collapsed on top of him.

Several people fell. Piles of people crushed those underneath in a 10-foot bloody area at the foot of the stairs. Coats and hats and shoes lay all about.

Haunting screams pierced the air.

The bordering chicken wire walls and stairway handrails cracked and snapped apart, and people tumbled from the top of the pile to the muddy floor below.

Thirteen-year old Isidore Simon immediately jumped from his Ruthville seat as soon as the mass exodus began. He quickly found himself raised upward and on to the heads of the mob scattering in front of him. In a terrifying moment, Simon was abruptly thrust through the chicken wire and onto the ground below, clear of the stampede. He lost his hat and a shoe in the ruckus, but walked away with only bruised shins and scratches to his face.

Simon was one of the lucky ones.

Many of the fleeing spectators, already soaked from the rain, were jammed so tightly together that they had difficulty breathing. Many of those, including a large number of young boys, were trampled by the frightened throng looking for an escape route from the madness. Panic-stricken mothers screamed for their children. Cries for doctors and nurses could be heard in chorus with the roaring thunder and lightning crashes above.

Soon, but not soon enough, many near the back of the pushing crowd began to realize the madness happening in front of them. They turned, looking for alternate exits while shielding themselves from the rain with newspapers.

Most of the spectators scattered throughout Yankee Stadium – those seated in the grandstand and in the seats along the baselines – were unaware of the calamity happening in the right field bleachers. Some unwittingly laughed at the scramble they were witnessing. The first sign of tragedy was the sobering sight of a “dead man,” the Hartford Courant reported, being carried across the ball field on a stretcher.

Some reports say Babe Ruth was among the first to realize, to an extent, the severity of the situation.

He yelled for help.

Stationed just outside the ballpark, at the River Avenue and 157th Street exit, were a New York City police captain and a group of policemen who were sent to the ballpark to help with crowd control when the sky began to darken.

A United Press International wire account, published in various re-writes in newspapers across the United States, relayed a story of Patrolman Louis Baer’s attempts to organize the mayhem by drawing his pistol. Baer ordered people to help him rip away the chicken wire, and as they did, the pushing became more violent. The Minneapolis Star published the same UPI story with one extra detail claiming the rowdy group shoved Baer, fracturing his ribs.

(It’s worth noting that a New York Daily News story from November 30, 1937, reported that Patrolman Louis Baer, at age 35, was killed when the driver of a stolen car crashed into Baer’s car at the corner of Brook Avenue and 146th Bronx Street. Baer suffered a fractured skull in the incident and died at Lincoln Hospital.)

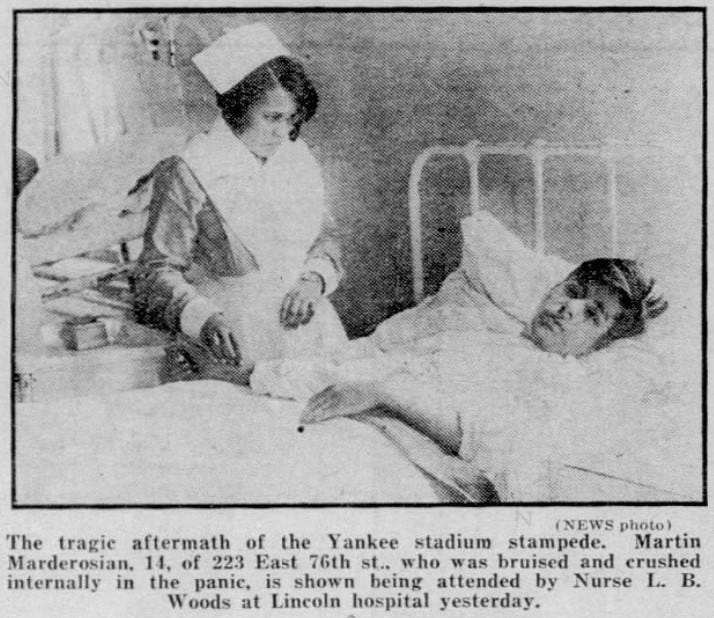

Police captain Louis Haupt and a group of his officers heard the commotion and rushed into the ballpark, discovering the maddening scene. They helped push the crowd back and pulled others to their feet. Some, they could not help so easily. Beneath the struggling heap at the foot of the stairs were several bruised and bloody figures with ripped clothes. Many began crawling away on their hands and knees.

A few were found unconscious.

One was Joseph Carter, the 60-year-old truck driver from East 128th Street in Manhattan. When police gently rolled him over on the muddy ground, Carter was already dead. A rain check was found in his shirt pocket, along with a chauffeur’s card that was used to identify his body. His death certificate, signed by New York’s first medical examiner Charles Norris, stated that Carter died of “bursting walls of chest” as a result of a “stampede from a crowd.”

Police searched all day for Carter’s son to notify him of his father’s death, but he was not home when police arrived. Officers asked his neighbors on East 144th Street to tell the son to visit the morgue to identify his father’s body.

Among those individuals lying in the mud near Carter was Eleanor Price and her brother, George. Both still were breathing, but Eleanor’s injuries appeared more dire. Two young men, William Thompson and Henry Mims, gently lifted Eleanor from the mud and carried her wounded body to the Yankees’ locker room. There, team trainer Doc Woods had set up a make-shift medical room.

The locker room was already full of frightened, young boys, many of whom were crying from cracked ribs and broken bones. Sympathetic ballplayers surrounded the suffering.

Ambulances with surgeons and nurses from Bronx hospitals rushed to the scene and fought their way to the injured. A few medical doctors were among the spectators and offered care. Police and stadium patrol personnel commandeered taxis, a large bus – it had been waiting nearby to take site-seers to Times Square – and other vehicles to transport people in need of medical attention. More than 50 people were taken to nearby Lincoln and Fordham hospitals.

Curious onlookers from the street gathered around, but police maintained order.

Probationary patrolman Elias Gottlieb had been sitting in Ruthville during the game. As soon as the accident on the stairs happened, he heroically rushed to the scene and carried victims to an area of the grandstand where a pile of bags were stored. The quick-thinking Gottlieb used those bags as cots until medical assistance arrived.

More than 300 police personnel worked the scene. Frank Roth and special officer Joseph Vincent were among those who performed in heroic fashion and were credited for saving many lives. Roth carried to safety 14 fallen individuals from the massive, twisted heap of humanity. Five of those were children. Vincent carried nine. He, the New York Times wrote, was helped by a Black man, who disappeared as soon as the injured had been removed.”

Back in the Yankees dressing room, Phillip Fruchtman, 13, who had sat among the Ruthville crowd for the game, tried to force a smile with closed eyes and swollen cheekbones as he talked to medical staff, newspaper men and gathered players. “I feel like a truck had run over me,” Fruchtman told them.

Morris Lerner had a broken bone ripping through the skin of his left arm, but he seemed more worried about his mother learning about his circumstances. “What’s the sense in scaring her half to death,” he said crying as Doc Woods wrapped the boy’s arm and a police officer wrote down his name and information. “Gee, you know how women are.”

It was heartbreaking for Ruth. He turned away with tears in his eyes. “Poor kid,” the slugger said as Gehrig and Bob Meusel gathered around. “I hope I hit 60 home runs this year and that kid sees all of them,” the Babe said.

Moments later, the 14-year-old Lerner placed his cap on his head and started the near-half hour walk in the rain back to his home on Trinity Avenue.

*****

Eleanor Price never walked away.

Yankees’ team physician Dr. John Fitch Landon arrived at the Yankees locker room from Roosevelt Hospital, where he was a staff member. He found Eleanor lying on a makeshift cot. She had been crushed at the bottom of a mass of bodies.

George had tried to save her, but he, too, was knocked about and trampled. He suffered a concussion and internal injuries.

Eleanor Price graduated from Evander Childs High School in February 1927 and, in May 1929, was studying geology at Hunter College. She had an interest in literature and served on the editorial staff of the Hunter literary magazine, Echo. Eleanor published more than 80 poems in the magazine.

She was the daughter of Dr. Max Price, the head of the general division at Union Health Centre. He and his wife had come to the United States 30 years before. In addition to George, Eleanor had another younger brother, Nathan, who was 9.

Eleanor was a passionate baseball fan. She had a bright future ahead of her before tragedy took it away.

When Dr. Landon arrived at Eleanor’s side, it was too late. She died just five minutes after being carried to the Yankees dressing room.

A policeman reluctantly and awkwardly searched for identification in her gray pocketbook. He found a cracked mirror and a card, issued by Hunter College, bearing her name.

Some reports claim Babe Ruth was holding Eleanor as she took her final breath, but there isn’t much evidence to support that narrative. The day after the stampede, Ruth sent a letter to those who remained in the hospital. “My special condolences go to the bereaved loved ones of poor Eleanor Price, who died,” he wrote. “I can’t tell you how sorry I am about her.” Ruth made no mention of holding Eleanor as she died.

More than 60 people were injured in the chaos. Eleanor and Joseph Carter were the only two fatalities. Reporting the story the next day, May 20, the New York Times claimed the two died from being “pinned under a struggling mass of humanity.”

*****

Patrons levied heavy criticism toward the Yankees and stadium operators immediately after the tragedy.

John Keane took his four-year-old son, Thomas, to the game because the young fella wanted to see for himself if the Babe really looked the way he did in photographs. The father and son were sitting in right field when the storm unleashed. In the mad dash, young Thomas was ripped away from his father’s grasp. People were “shouting and screaming,” he later told newspaper reporters at the scene.

“Two policemen and some colored boys worked hard to calm the crowd and helped rescue a lot of people,” John Keane told reporters. They were laying the injured out in rows when I found my boy and left.”

Keane, an accountant from the Bronx, blamed part of the tragedy on stadium workers not opening a large wooden gate that would have alleviated some of the pressure from the rushing mob.

Yankees owner Col. Jacob Ruppert denied the gates were closed. “They are always open the minute it starts to rain when a game is in progress because there is always a scramble for the gates,” he said. “But, usually the rain isn’t so sudden and the people have more time to get out.

“It was an unfortunate accident,” the colonel continued. “But it couldn’t be helped.”

A conspiracy theory, if you will, claimed the Yankees, who were 3-0 winners in the rain-shortened contest, urged umpires to prolong the game in hopes of not having to hand out rain checks that would allow fans to see another contest for free. “Greed and money,” cried George Salmonowith of Brooklyn and Louis Rosenberg, a Bronx druggist. They felt the game could have been stopped in the fourth inning when a drizzle began to glisten the ballpark.

Others claimed the Yankee organization, too, was holding out until Ruth and Gehrig got one more chance to thrill the crowd in the bottom of the fifth inning. Imagine the scene if Ruth, instead of grounding out, hit one more clout to Ruthville just as the rain began to pour and ominous storm clouds loomed.

The Yankees took no responsibility for the incident. Instead one team representative shifted blame on the youthful Ruthville residents.

“It was just a case of the crowd losing control of itself in the rush to get out of the rain,” team secretary Edward Barrow speculated. “When those in front fell, the others were pushed on by the jam behind.

“A bleacher crowd, too,” Barrow continued, “is usually made up of young fellows, and there probably was a lot of shoving and fooling – as youngsters will do – before they realized how serious the matter was.”

Barrow’s comments came just as District Attorney John E. McGeehan cleared the Yankees of any liability a day after the incident, and minimized the stampede as “a wild rush of people down a narrow chute without apparent reason.” (In December 1932, the Yankees settled a lawsuit with 34 plaintiffs, including family members representing Eleanor Price and Joseph Carter.)

Even less sympathetic words came from a man named Joseph Condon, who wrote a letter to the Daily News claiming “the Yankee stadium [sic] panic undoubtedly started because a lot of nuts were afraid of getting their $1.95 straw hats wet.”

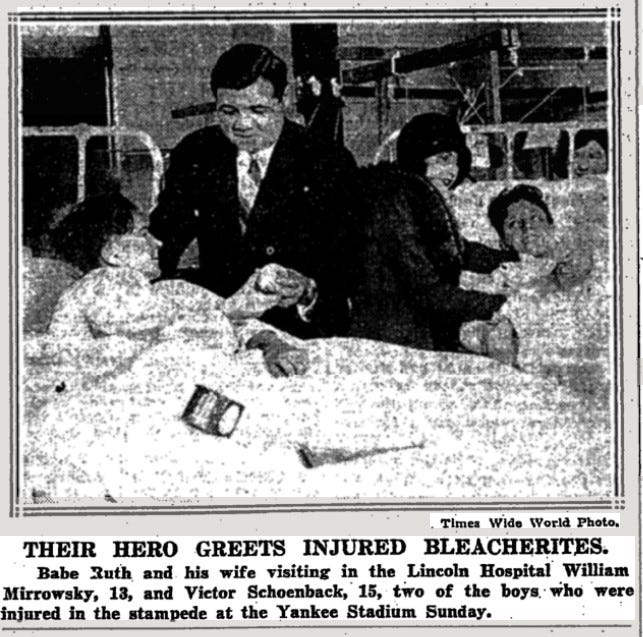

The Babe, Ruthville’s namesake, however, demonstrated heart and class to the ailing. Two days after the incident, Ruth, his wife, Claire, and a handful of photographers visited youngsters still recovering in Lincoln Hospital. He brought with him two boxes of baseballs and a fountain pen.

Among the most seriously injured was 11-year-old Bronx native Leon Geffner, who suffered a fractured skull as he lay at the bottom stampede pile. He was unable to speak as Ruth entered the room. He blinked a couple of times and began to cry.

“Were you in that crush?” Ruth asked.

Geffner nodded in the affirmative.

Fumbling for words, Ruth looked down at his young admirer, signed a ball and gently placed it on Geffner’s cot as he walked away.

Thank you for reading ppd – rain. This post is public so feel free to share it.

And now, for a check on the weather with meteorologist Kevin Kloesel

Way back in 2017, about a year after I began researching the Yankee Stadium stampede, I spoke on the phone with Kevin Kloesel, a meteorologist with the University of Oklahoma Department of Campus Safety and a super cool guy to talk with on matters of weather and public safety. Kloesel has done far more intellectual and scientific research involving the stampede than I ever could.

When we spoke, I asked Kloesel if there was a way, based on historical weather data, to determine characteristics of the storm that hit Yankees Stadium in 1929.

“I’m guessing because of the longevity of it – based upon the records – it leads me to believe that it was a derecho event,” he said. “We’ve seen derecho events like this before with similar circumstances. So, that would be my best guess as to what happened.”

Kloesel said the storm – again, based on historical data – reminded him of the weather event that caused a stage to collapse at the Indiana State Fair on August 13, 2011. “I would envision it looking almost identical,” he said.

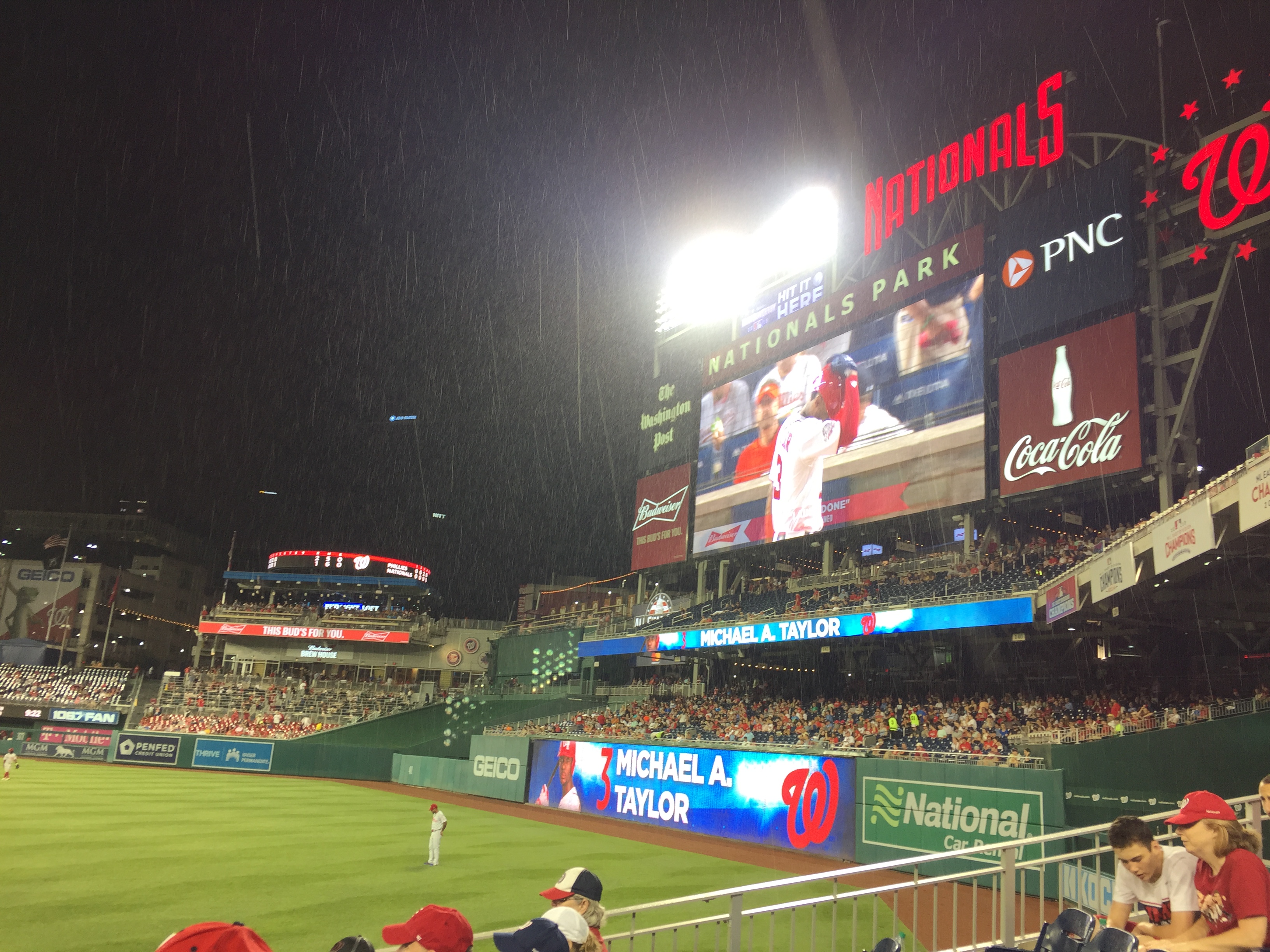

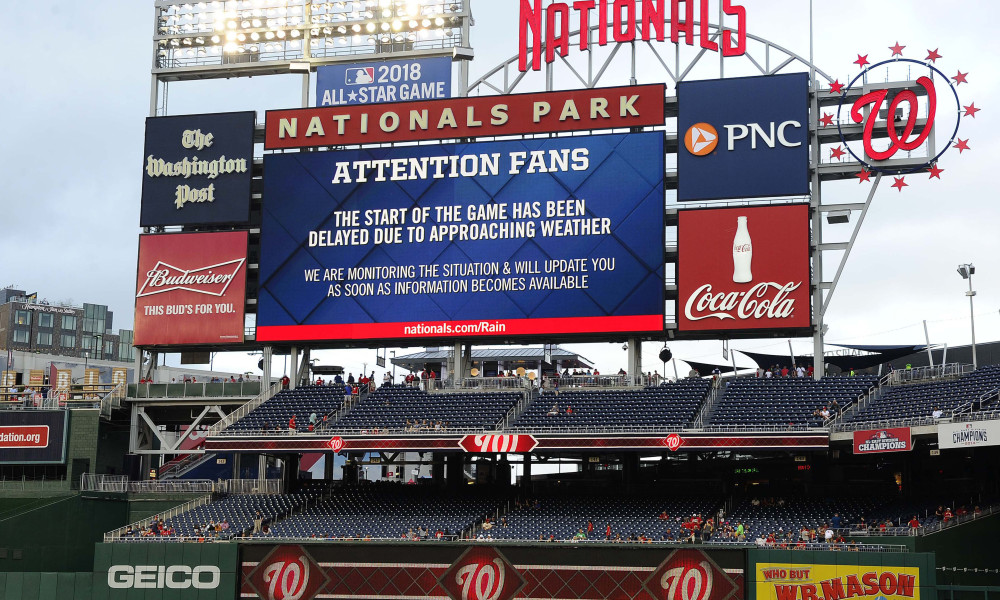

Mitch Haniger’s wild game-winning home run in Seattle last week – as the roof was closing and rain was falling in the ninth inning – reminded me of a contest three years ago when the Miami Marlins had a similar weather situation at their relatively new ballpark.

Mitch Haniger’s wild game-winning home run in Seattle last week – as the roof was closing and rain was falling in the ninth inning – reminded me of a contest three years ago when the Miami Marlins had a similar weather situation at their relatively new ballpark.